Each Monday, I’ll be breaking down a recent development affecting the economy of the movement of people and goods. To follow along for the journey, enter your email below to subscribe.

🗽🍎 In NYC for Climate Week? Shoot me a line!

Did you see the follow-up to last week’s MobilityMonday issue?

United announces free internet connection through partnership with Starlink and its armada of low-Earth orbit satellites

I landed in NYC yesterday for Climate Week, and while I didn’t tap into El Al’s Wi-Fi offering during the 10-hour red-eye flight and instead opted to catch some Z’s, recent developments in airplane wireless internet connection have not been something to sleep on.

A little over a week ago, United announced a partnership with SpaceX’s Starlink subsidiary to provide free internet connectivity to its fleet of 1,000+ aircraft. While the ramp-up will take at least a few years, this marks a major milestone in the timeline of in-flight connectivity, but also satellite internet technology more broadly. (In late 2023, Qatar Airways became the first airline to announce a partnership with Starlink)

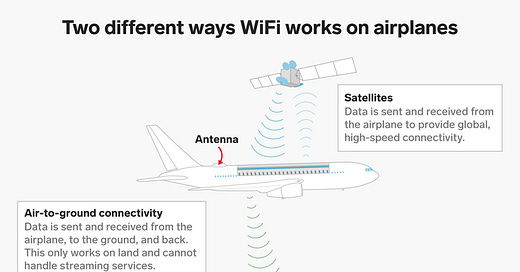

The first major attempt at providing in-flight internet was Boeing's Connexion service, launched in 2000. However, the hardware and antennas needed weighed nearly 1,000 pounds, thus adding too much drag and weight to the aircraft to be commercially feasible. In the late 2010s, players like Gogo began to offer air-to-ground networks, which essentially created cellular networks pointed at aircraft, and later, satellite-based systems emerged as well.

Until now, United has enlisted Wi-Fi services from four satellite providers — Gogo, Panasonic, Thales, and ViaSat — across different geographies and aircraft.

As opposed to cable, satellite internet offers greater geographic coverage but suffers from higher latency. Airlines can also leverage comprehensive datasets to optimize satellite positioning and bandwidth allocation for specific routes in order to provide optimal Wi-Fi services.

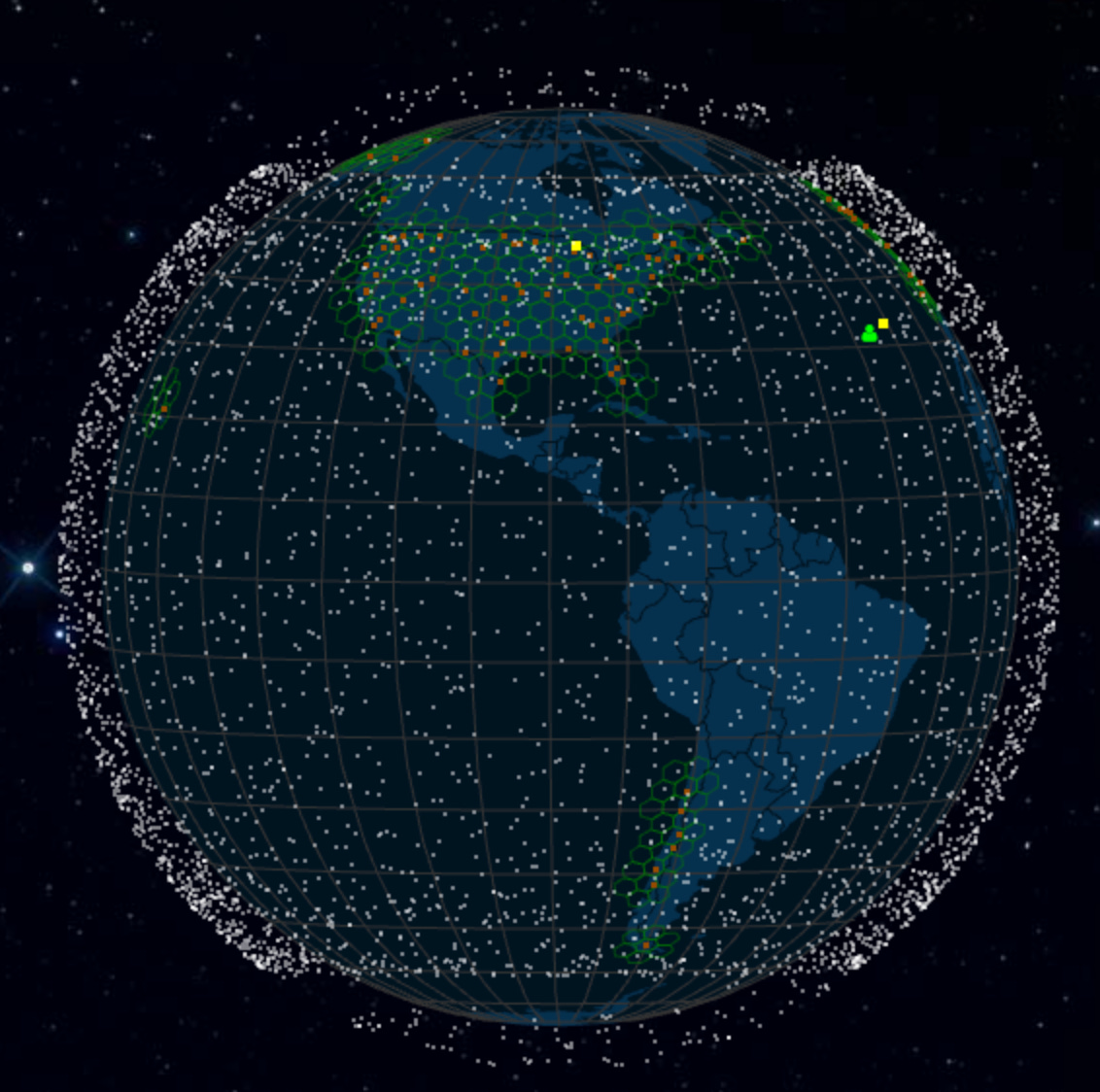

However, the existing satellite providers have a much smaller footprint than Elon Musk’s Starlink. Today, the company accounts for a whopping 60% of all active satellites in space today, having skyrocketed (spacerocketed?) from a little over 350 satellites in orbit at the dawn of the COVID-19 pandemic to nearly 2,000 only two years later. Starlink in particular has been a pioneer in low-earth orbit (LEO) satellites — those operating less than 1,200 miles above the Earth’s surface.

The proximity of LEO satellites to aircraft enables lower latencies, more capacity, and higher internet speeds. In addition, the satellite terminals needed to retrofit aircraft to enable Starlink connectivity are much smaller and easier to set up than existing hardware stacks.

All this occurs against the backdrop of increasingly demanding consumer expectations and advancing terrestrial internet connectivity. A 2021 survey showed that 75% of passengers consider Wi-Fi important during flights and that two-thirds of airline industry stakeholders believe that airlines should cover the cost of in-flight Wi-Fi as opposed to passengers paying for the service themselves.

Over the coming years, Delta is rolling out free Wi-Fi on select international routes in partnership with T-Mobile. Australia’s Qantas is also doing the same, in partnership with Viasat.

So what does the future of mile-high internet hold? The democratization of the internet is reaching new heights in both the literal and metaphorical senses, and it may not be long before in-flight video calls and Netflix streaming are commonplace. And at a higher level, aerospace technologies are becoming increasingly intertwined with terrestrial demands, be it in regards to internet connectivity, new materials, climate change abatement, and more.

👜 Grab Bag

Gogoro CEO resigns as subsidy fraud investigation continues

Germany lobbies fellow EU members to vote against tariffs on Chinese EVs